Published: May 27, 2025 at 10:45 AM

Let’s take you on a crash course

ORLANDO, Fla. – We’re virtually on the edge of diving overboard into the 2025 hurricane season. The Eastern Pacific is already underway and on the verge of producing its first named storm. What about the Atlantic? Will Andrea be spinning up anytime soon?

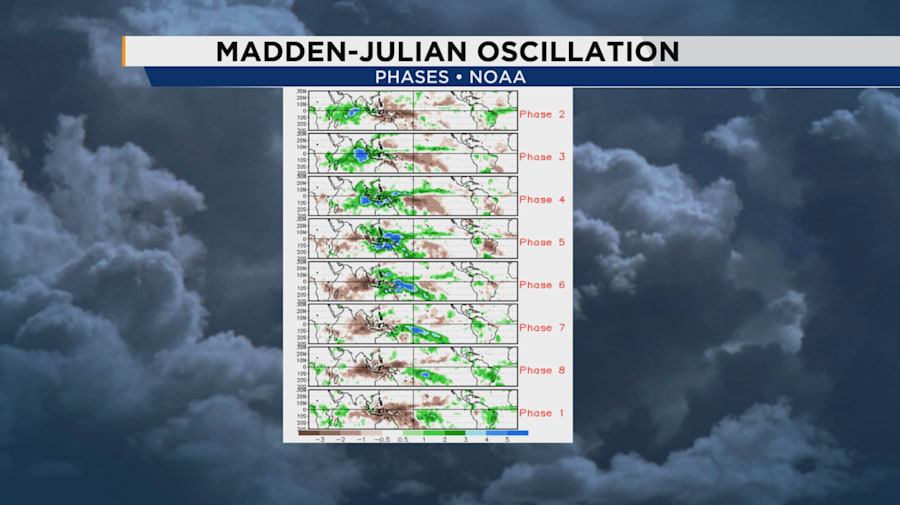

One of the most pertinent “intra-seasonal” variables we monitor as meteorologists is called the Madden Julian Oscillation. This is what drove a lot of our action close to home last hurricane season.

This same phenomena produced Helene and Milton almost entirely, alongside a few other pieces of the tropical puzzle.

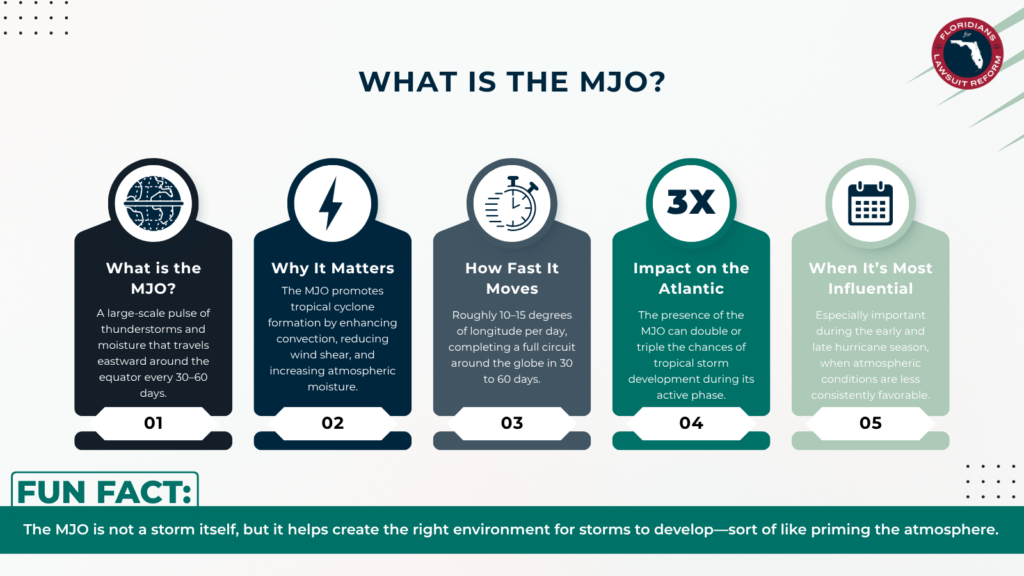

The Madden Julian Oscillation is commonly referred to as the “MJO” for short.

In its most basic definition, the MJO is a wave that moves west to east across the tropics or along the equator over time. It quite literally behaves like a wave you’d see in water after a splash or along the shore when you’re lounging at the beach.

As it moves through, it helps to generate lift, moisture and, of course, tropical rains. It tends to revolve through its phases on a basis of 30 to sometimes 60 days, or one to two months. Several factors can affect its progress eastward like ocean temperatures and the jet stream.

Why is this so important to the hurricane season?

We’ll use last hurricane season as an example. The MJO tends to move across the tropical Pacific first, originating in the Indian Ocean immediately east of Africa. As it moves through, we can use several different graphics or diagrams to see its current position.

Typically when it starts to arrive in the East Pacific, and especially the Central America region, models get “excited” and begin showing us the potential for tropical cyclone formation.

This is where it becomes a tedious task for meteorologists to accurately predict when and where a tropical system will form, if it does!

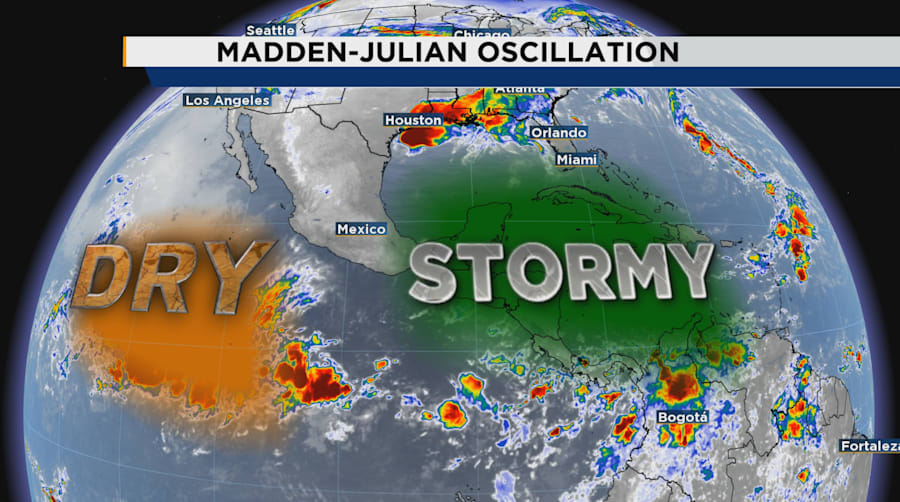

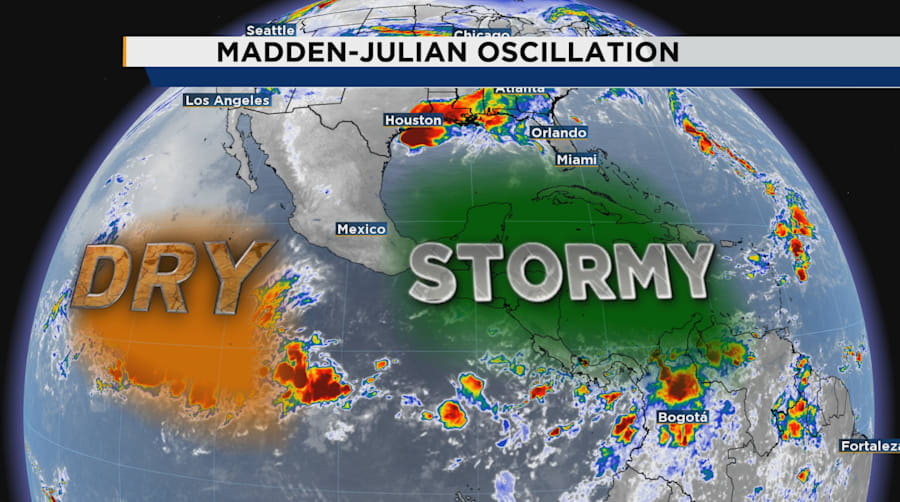

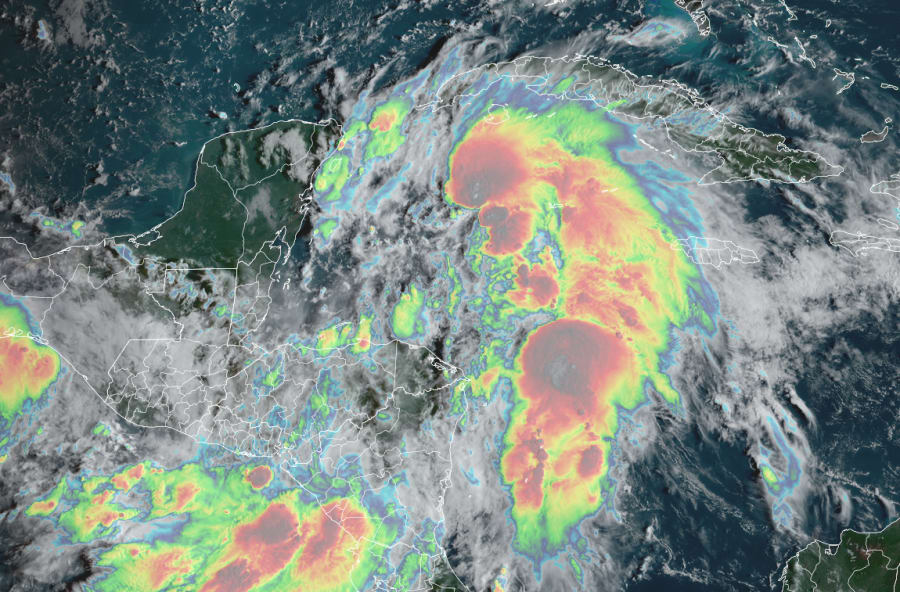

We naturally have an annual flow of winds across the Gulf, the Caribbean and Central America into the Pacific. When the MJO moves across, it disrupts this pattern and creates generally lower pressure across Mexico, Central America and sometimes as far east as the Central Caribbean Sea. When this happens, it’s almost inevitable we’re going to see rain and storms building resulting in flooding and mudslides for our folks down there.

Some of this moisture can try to balloon northward toward us in Florida.

If there’s enough energy or spin in the atmosphere, we can also randomly shoot out tropical systems like a sprinkler head zipping back and forth on your lawn.

The most notable of our tropical features to form during the MJO’s presence, were Helene and Milton last hurricane season.

That’s exactly what took place last hurricane season with several of our named storms that formed way too close for comfort.

Alberto and Chris, early in the hurricane season, came from tropical waves that first plopped off the west coast of Africa and slowly trudged through the Atlantic. By the time they arrived in the Caribbean, the MJO was in full effect producing rising motions and helping to plow the area of any dust or dry air that inhibits tropical development.

That’s how we ended up with our first named storm, Alberto, on June 19, 2024. Chris would go on to be a short-lived tropical cyclone in the same general area thanks to our MJO helping act like a “pre-workout” supplement for this little wave.

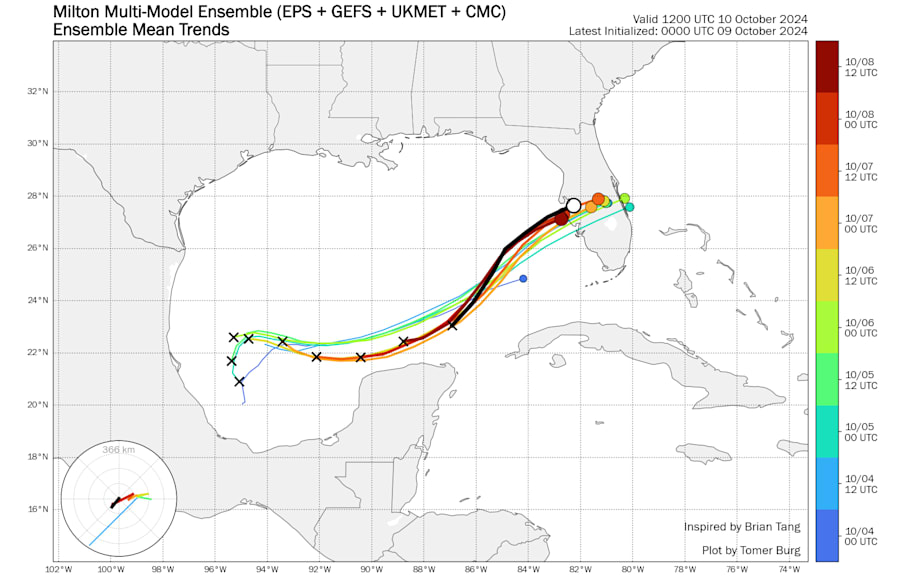

Sometimes it can be even trickier to forecast what occurs with the MJO and how it generates potential tropical storms. Milton was an EXCELLENT (and destructive) example.

Another tropical wave late in the season wandered off Africa through our Atlantic basin. According to National Hurricane Center, we also had an area of tropical energy in the eastern Pacific trying to further develop as the MJO parked overhead.

But since we were so late into the year, we also had an aggressive jet stream dipping south over the U.S. When this occurs, it’s like metal to a magnet, and energy toward the equator gets tugged northward. As such, the wave that would go on to become Milton was sucked into the Bay of Campeche alongside Tropical Depression 11 in the eastern Pacific.

This mashing of tropical moisture and rotation generated what then exploded into Category 5 Milton moving through the Gulf.

There are eight known phases of the MJO, and typically when we’re in phases 1 and 2, sometimes into the third phase, we see Atlantic tropical weather favored. Outside of these phases, the influence is negligible and toward the back end of its phasing actually suppresses storms in our Atlantic Ocean.

We have several different maps we use throughout the year when predicting tropical weather and even severe or winter weather. You’ll probably see a number of these used throughout the hurricane season ahead. I myself have found great success in long-range tropical forecasting when carefully examining the latest MJO forecasts alongside model trends over a length of time.

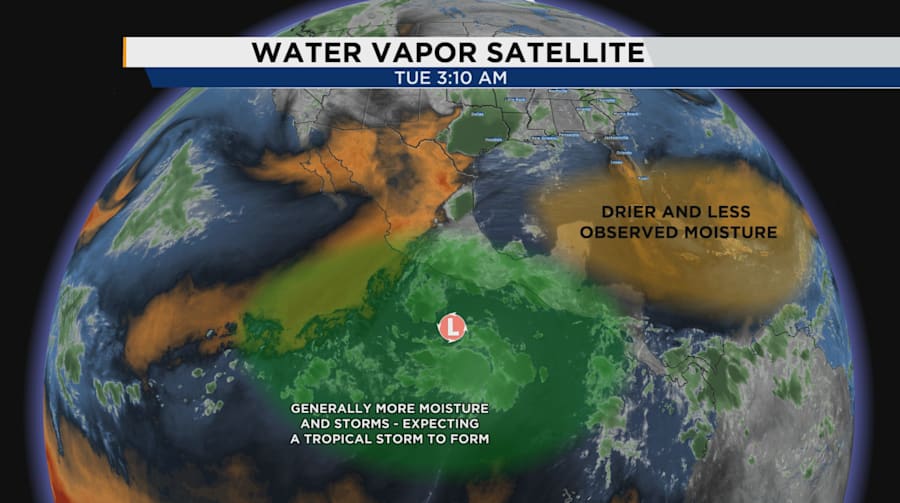

We’re still closely watching our Caribbean and Gulf for the potential of our first named storm as we go through the mid portions of June. Beginning around June 5 and running toward the 18th-19th appear to be the sweet spot for tropical growth, if a disturbance or a wave decides it wants to take advantage of the environment.

Copyright 2025 by WKMG ClickOrlando – All rights reserved.